Muslims remained suspicious of philosophical enquiry. Kalam, rather than philosophy became the most important subject in the madrassahs.

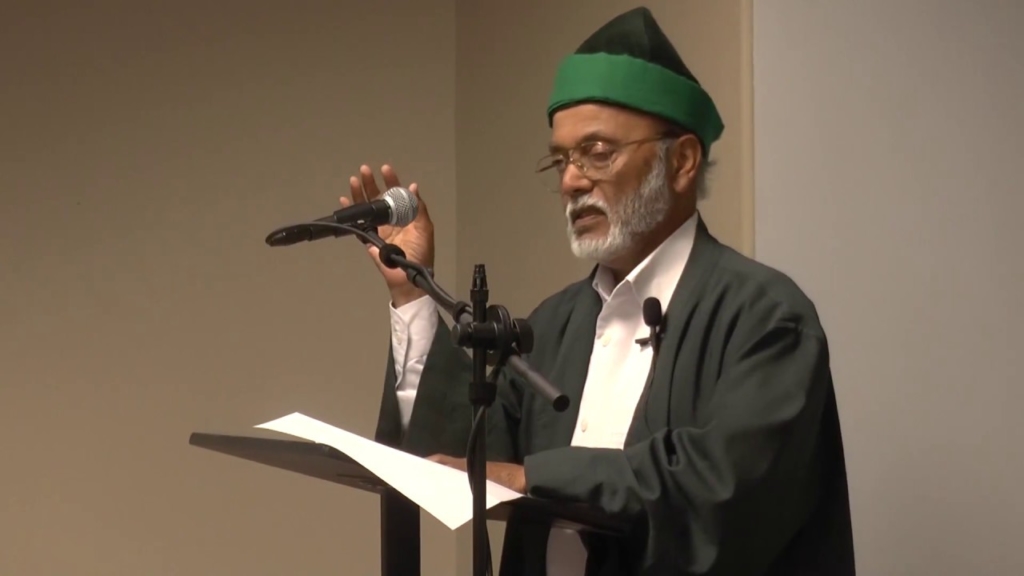

Reviewed by Nazeer Ahmed[1]

In Chapter 2, The Rise and Decline of Science in Islamic Civilization, Professor Ayub Omayya presents an incisive historical analysis of science and culture in Islamic societies. He observes that “the rise of science in the Islamic civilization was the direct consequence of the unique transformation of human minds by Islam”. The decline of science, he notes, was due to both external and internal causes. Among the historical external causes, he notes the Mongol invasions, the Crusades and tribal and internecine warfare amongst Muslims themselves. The more recent external causes include the conquest of Egypt by Napoleon, of the Moghul Empire by the British, the destruction of the Ottoman Empire and the subsequent Balkanization of the Middle East. But it was the internal mechanisms themselves that resulted in the death of a scientific culture in Muslim lands.

Noteworthy among the internal reasons were: the appearance of incompetent Sultans among the Ottomans, the rise of a centralized, despotic and severely restrictive orthodoxy, the discouragement of innovation in the trade guilds, conspicuous consumption among the ruling elite, an exploitative tax structure, the disappearance of the spirit of Ijtihad, and ignorance about the science and its relation to religion. Professor Omayya correctly makes the astute observation: “The greatest potential asset of Islam is the frank sense of history that from the start has been a dominant fact in its discussions, even though some modernizing Muslims have displayed a romantic disregard of historical facts”.

In Chapter 3, Professor Shaukat Ali presents a brilliant analysis of the decline of science in Islamic civilization. Going beyond the disappearance of Ijtihad as a tool for continuously shaping human society, Professor Ali presents a detailed analysis of the rise of the ulema “as a very closed and powerful elitist group”. He observes that during the first hundred years of Islamic history, the ulema did not enjoy any significant role in the Muslim society. Indeed, Islam frowned upon the emergence of a priestly class. This pattern changed with the introduction of Greek learning. The complexity of philosophical enquiry required the institutionalization of learning.

Madrassahs and universities emerged in the far-flung corners of the Islamic world. The acquisition of knowledge became the privilege of a few while the masses grew increasingly ignorant of the changes sweeping the educational landscape. The acquisition of knowledge by a privileged few brought them close to the ruling classes. Corruption followed. Barring a few notable exceptions, the ulema became sycophants in the courts of tyrants and imbeciles. This pattern continued down to the eighteenth centuries, when a technological backward Islamic world came up against an expansionist Europe and came out second-best in the contest for power.

Professor Ali notes correctly: “Another possible cause for the decline of scientific enquiry in Islam could be the ultimate triumph of the science of theology over other sciences”. Even at the zenith of its classical civilizations, Muslims remained suspicious of philosophical enquiry, a hangover from the excesses of the Mu’tazilites. Imam al Ghazzali’s diatribe against the philosophers won over the Islamic world and withstood the rearguard defense of Ibn Rushd. Kalam, rather than philosophy became the most important subject in the madrassahs. Bereft of the precision of logic and mathematics, the sciences withered and finally made an exit through the back door as the sciences of fiqh filled the emerging vacuum. Where the scholars once pondered the nature of man and nature, the latter day scholars indulged in endless debates about esoteric and inconsequential legalisms.

Among the other reasons advanced by the author for the decline of science, mention should be made of the dependence of scholars on royal patronage which rose and fell at the whim of the ruler, the disappearance of critical research and the degeneration of scholarship into acquiring some information about the works of bygone writers and the absence of the printing press. As quoted by the author, “the inevitable result of such a system, over which no quickening breath had blown since the beginning of the sixteenth century, was to intensify both the narrowness of the educational range itself and its narrowing effect on the minds of the educated”.

A great deal more work remains to be done in this field. The book is a timely contribution to the history of science and culture in Islam and would benefit the youth who are hungry for knowledge about the own past so that they can charter their course for the future.

End.

Before:

Footnotes:

[1] Professor (Dr) Nazeer Ahmed is President of American Institute of Islamic History and Culture, Corcord, California